This interview is freely available, but most here aren’t. If you enjoy it, please consider subscribing to receive access to all the exclusive content on this web site – over a hundred recorded interviews, plus meditations, teachings, essays, and research projects. Not only will you gain a huge archive of esoteric material, but it’s a great way to support Occult of Personality podcast.

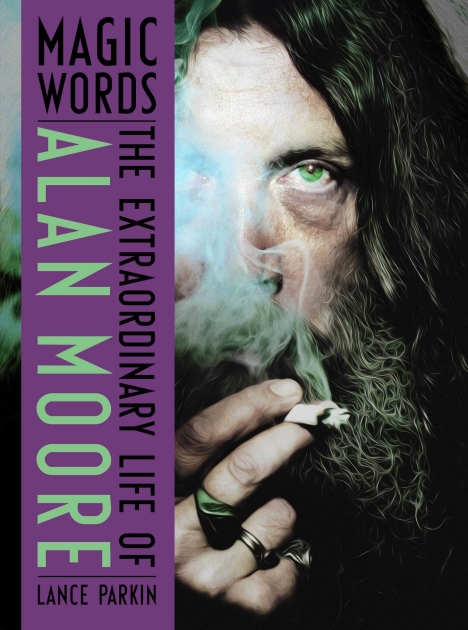

After reading Lance Parkin’s excellent biography, Magic Words: The Extraordinary Life of Alan Moore, I invited him for an interview to discuss the magickal aspects of Alan Moore and his work.

“For over three decades comics fans and creators have regarded Alan Moore as a titan of the form. With works such as V for Vendetta, The Watchmen, and From Hell, Alan has repeatedly staked out new territory, attracting literary plaudits and a mainstream audience far removed from his underground origins. His place in popular culture is now such that major Hollywood players vie to adapt his books for cinema, regardless of his contempt for their attempts. Yet Moore’s journey from the hippie Arts Labs of the 1970s to the bestseller lists was far from preordained. A principled eccentric, who has lived his whole life in one English town, he has been embroiled in fierce feuds with some of the entertainment industry’s biggest corporations. Just when he could have made millions ploughing a golden rut he turned instead to performance art, writing erotica, and the occult. Now, as Alan Moore hits sixty, it’s time to go in search of this extraordinary gentleman, and follow the peculiar path taken by a writer quite unlike any other.

“Now, in anticipation of his 60th birthday, Moore aficionado Lance Parkin goes in search of this extraordinary gentleman, and reveals a writer quite unlike any other working today.”

Occult of Personality: Would you please describe your interest in esotericism? Is this a subject that interested you prior to your engagement with Moore’s work? How would you characterize your perspective on the subjects of mysticism, magick, and metaphysics (e.g. believer, skeptic, journalist)?

Lance Parkin: Personally, I’m not a religious, spiritual, supernaturally, mystically-minded person at all. It’s never been part of my life, and I’ve never felt it as a gap in my life, or really even engaged with it sceptically, either. But I do read, I do enjoy a great many things that have been created by esoteric artists.

My perspective writing this book was that it’s a major part of the life of my subject, and that the author of a biography will never hold exactly the same opinions as the subject of the book. Practically, the vast majority of my audience would need some help navigating the terrain, while a significant minority who were engaged with the occult wouldn’t want to be bored stiff for a chapter being told stuff they knew already. And that to understand Moore, I had to engage with something that’s been a major part of his life for at least twenty years.

OoP: Your interest in Moore’s work stretches back several years. Why do you find Moore’s work, as well as the man himself, so compelling?

LP: I think for a lot of people, an interest in a particular band, or writer, movie or director, stems mainly from a coincidence of timing. I like Star Wars because I was six when Star Wars came out, and haven’t had much time for Harry Potter because I was thirty. Alan Moore wrote some memorable back up strips for Doctor Who Weekly when he was starting out, and I read that. I recognised his name when I saw it in 2000AD, when I accidentally picked up a copy of Warrior, when I discovered American comics and saw he’d started writing Swamp Thing.

There’s something distinctive in the rhythms of his work, like a fingerprint, that means that whatever he’s writing – and some of those early gigs are the lowest rung of the ladder, even for hacks – it’s clearly him writing it. He can make the silliest ideas (his own and other people’s) just work. There’s great technique, great attention to what he’s doing but he always – or at least a lot more always than most people who’ve written as much as he has – creates a story that propels itself along.

OoP: Why did you decide to write the biography of Alan Moore?

LP: At root, this is a literary biography, it’s about his body of work, his career and how his interests have developed over time. He’s written a lot, and you can see his work develop as he goes, and we can see a story of a writer who looks very peculiar with his beard and snake-head cane and so on, and whose work is very distinctive, very personal, but who wrote for mainstream comics, the business end of which is a corporate controlled production line. He didn’t work in a vacuum, but it’s fair enough to say that he invented the idea of taking a long-running series and re-imagining it as a darker, more adult, more ‘realistic’, more poetic version. And the idea of ‘rebooting’ a long running or dormant franchise along those lines is everywhere, now. He’s ridiculously influential, you can see clear lines of descent, often direct quotes from his work, across pop culture, in things like The Incredibles, Lost, True Detective and Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

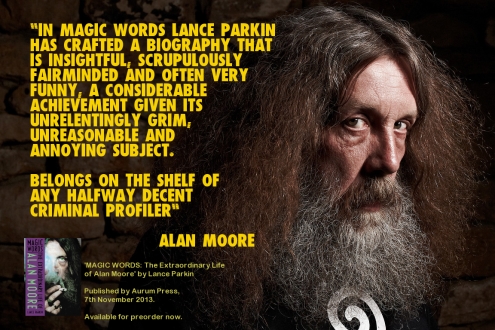

OoP: Moore endorsed the book and I’m wondering about your thoughts on his approval, as well as his involvement (or not) in the writing process. How much was Mr. Moore involved in the composition of your book?

LP: Once the manuscript was completed (around the end of June last year) my publisher sent him a copy out of courtesy. Moore knew I was writing it, and at the beginning of the process, about three years before, had said – very politely – that he wanted nothing to do with it, and anyway that unauthorised biographies are always more fun. I wrote the book I wanted to write. He’d asked me not to hassle his friends or family, and the net effect of that was that instead I talked to a lot of people who’d fallen out with him or otherwise lost touch over the years. I tried to be fair. Where there were two sides to a story, I’d do my best to give a fair account of both sides. When you sit down and lay out the timing of events, you find little discrepancies and elisions in people’s stories. That’s inevitable, I think. We neaten up our own life stories.

Alan Moore liked the book, he liked it to the extent that he agreed to come to the launch party, which then – at his suggestion, as I understand it – morphed into a big Evening With event in London and suddenly I was on the West End stage in front of 250 people, including some of his best friends, asking him impertinent questions. There’s a recording of that here: http://popculturehound.net/episode-66-the-magic-words-of-alan-moore-lance-parkin/.

So I’m in a weird place where I wrote an unauthorised book, but one that’s endorsed by its subject. To be honest, OK, I think that’s brilliant and I am very grateful to Alan Moore that he’s supported it, but other people saying they like it has meant as much. Dez Skinn – Moore’s editor on Warrior, where he did the early strips Marvelman, V for Vendetta and The Bojeffries Saga – had a spectacular falling out with Moore, a feud that remains one of the notorious open wounds in the comics industry, and he also thought it was a fair account. So this isn’t Moore’s side of the story, where there’s a dispute, I’ve tried to get across both positions. There are various people with all sorts of opinions about Alan Moore who recognise what they read. That was the anxiety, that someone would go ‘wait, that’s not right, at all’ or ‘there’s this whole side you’ve missed, which is … ’

OoP: Would you please tell us about the design choices for the physical version of the book? It’s quite a visual masterpiece and unique in the illustrations and colors.

LP: Aurum pulled out all the stops, and this is a part of the process which I had very little, if anything, to do with. I was always keen that it avoided the ‘comic book’ cliches and looked like a proper biography. Talking to Sam Harrison, my editor, I offered the opinion that in the era of the ebook, every physical book these days needs to look like McSweeney’s published it, it really has to feel nice and well made and be an interesting object.

Aurum put together some nice books. When I popped in to Aurum last May, I was shown various possible formats, saw other books they’d published. Sam was keen to make it a little shorter and wider than the industry standard, just to make it stand out a little on the tables in bookshops. I approved the cover image over a very pleasant Thai meal, and thought the end result was just going to be a perfectly respectable standard hardback with a dust jacket. Instead it’s this … it’s difficult to describe. I opened the envelope my first copy came in, and was just wowed by this very striking book, with loads of fun little features. All sorts of things you don’t see in photographs of it, too, like Moore’s eye on the front cover glints if you angle the book.

As I understand it, and I may be wrong, it looks as lavish because we decided fairly late in the day that there wasn’t much point having a photo section in the book. It’s got a lot of illustrations in the main text. We’d originally planned on having a photo insert, too. But for various reasons, we just agreed that the material wasn’t necessary. Gary Spencer Millidge’s Storyteller is a coffee table book about Alan Moore with every possible picture of Moore himself, panels from his work, covers, original art and so on … it had covered that angle. When we were looking for illustrations for the body of the book, we really had to strain to find anything that wasn’t just in Storyteller (in the end, about half of them aren’t!). But we didn’t have any great, compelling pictures in colour. So there was some spare cash in the design budget. So it looks like a proper biography, but it’s a little weird. Which is thematically appropriate. It’s sold really well in hardback, too, to the point they’re delaying the paperback a while. People clearly want to own this edition as an object.

OoP: Would you please share with us the manner in which you classify Moore’s magickal belief system into 3 key components? What are the component classifications and how do they apply to Moore’s work?

LP: I break it down into three areas, and they’re clearly all connected. The one that feature writers like, because it sounds the weirdest is that Moore worships Glycon, a snake god from the second century Roman Empire. Moore’s aware how silly it sounds, and that’s part of the point – a big part of Moore’s endeavour is that he’s being playful, that he’s exploring a playful realm. Which is not to say he’s not sincere, or that he doesn’t take it seriously. As Terry Pratchett said, the opposite of ‘funny’ isn’t ‘serious’, it’s ‘unfunny’. Moore is seeking to explore what he calls Ideaspace, essentially ‘the realm of the imagination’, and he needs a guide like Glycon and maps like the Qabalah to provide some sense of structure. But Moore’s not just off in a puff of smoke, he’s deeply concerned with rooting all this into what we’d normally call reality – the practical effect is that it helps his creative process, but he also seeks to anchor Ideaspace to an intense localism, one that’s a riff on Iain Sinclair’s work with psycho-geography. He’s always lived in Northampton, which is – forgive me, Northampton – on the face of it an entirely unremarkable town in the British Midlands, but which, like anywhere, has fascinating history, it has weird place names, it has famous sons and visitors, it’s touched by war and politics, its fortunes rise and fall. And the more you dig, the more coincidences you find, the more connections. And so Moore comes to appreciate the place he lives at these extraordinary levels, as he walks the terraced streets, or goes to the shopping centre or whatever, he’s seeing the town where he lives in a richer, more colourful, deeper way than anyone else. He’s actively engaged with it, with its history, its people, its class politics, its geography. And, to paraphrase Moore, if that’s madness then who’d be sane?

OoP: Would you describe Moore’s use of psychedelic mushrooms and how that dovetailed into his magickal workings?

LP: Northampton lagged a little behind London when it came to the latest trends, but he was really connected to current American pop culture as a result of his love of American superhero comics, and those comics went through a real psychedelic phase in the late sixties and early seventies. So Moore’s slightly too young and slightly too late to be a hippie, but becomes one anyway. He started taking a lot of LSD when he was sixteen, was expelled from school on suspicion of drug dealing about a year later. He’s made no secret of the fact he’s continued to use drugs of various types. The back cover of the book has him wreathed in green smoke and he saw that and said he’d never puffed on anything that made green smoke, but if anyone could find him any, he’d be happy to give it a try.

His early workings involved mushrooms. He’s said that he doesn’t really use them that often any more, as he was using them to relax and get into the right frame of mind – or wrong frame of mind, I’m not sure quite what the bearings are, there. He can ease himself into that state unaided now, apparently.

OoP: How does Moore differentiate himself and his magickal beliefs and practices from most other occultists?

LP: Moore’s a writer (and occasional artist and musician), and you can’t separate his art from his magic. His work since the early nineties, even the more mainstream stuff, has been part of the same project. At one level, the one I find easiest to relate to personally, it’s a name he gives his creative process, it’s a brainstorming exercise to do that twin thing you have to do as an artist, which is go wild and crazy and out there, but to maintain some sense of order and structure. Ultimately, stories aren’t just about the wild ideas, they’re about the frame you mount them in. Moore’s own work immediately before his magical epiphany was incredibly rigid, incredibly structure. If you look at Watchmen, you can see it’s constructed like clockwork, and there’s work like Big Numbers, his (uncompleted) follow up project to Watchmen that was even more elaborately constructed. And he was beginning to find this restrictive and stifling.

So everything since has been a little more freewheeling, structurally, but is underpinned by … um, the same operating system, I guess. It’s most obvious in some of the bits of From Hell, or League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century and particularly Promethea, which are explictly about the occult and having visions and performing magic. But it underpins things that look more straightforwardly biographical like The Birth Caul or Unearthing.

Moore sums up his position in an essay called ‘Fossil Angels,’ and he basically berates practicing magicians for the same sins he berated comic book writers for in the eighties – it’s easy to be lazy, to be cliched, to mindlessly repeat the superficialities and trappings without looking a little deeper, it’s easy to exist in your own little bubble. I think the striking idea in that essay is that there’s a real danger in seeing magic as a sort of rival to science, as having that kind of explanatory, results-driven focus, and instead it should be seen as art, and judged on the artwork it produces.

And at one level it’s intensely private – he’s not doing it to go to gatherings or to make new like-minded friends. At the other, he’ll go on TV and talk about it. Or, notably, he’ll be interviewed by a magazine and suddenly declare, and this is a direct quote, ‘I’m a wizard and I know the future’.

OoP: What is Moore’s Ideaspace? What existing concepts might we use to properly relate to it?

LP: Moore sees what I think most people would call ‘the world of the imagination’ as a place we visit, one that connects up associatively, rather than geographically. A lot of his rituals seem to be almost hiking expeditions into this ‘Ideaspace’. Over the years, Moore’s depicted this in comics as an expansive, radiant domain that’s divided up into distinct areas governing by different principles, like Love or Justice. And it relates to the mundane world, but imaginatively. So we’ve got the North Pole and South Pole, and in literal terms, by definition, they’re as far apart as can be, but imaginatively they’re easy to link, to place together. And Moore’s point is that’s how we always operate – what we see as reality is our individual sense perceptions coupled to a brain that’s using memory and instinct to piece it all together into a seamless story we’re telling ourselves. Which we then reinforce by comparing notes with other people. We’re clearly physically fragile and tiny compared to a vast, indifferent distinctly Lovecraftian universe. At the same time, we’ve done all right for ourselves, given that we’re all (in Moore’s words) basically just mud that sits up, has a look around for a few years then reverts back to mud.

OoP: Would you please describe Moore’s contacts with entities that some may consider non-human intelligences? How would you characterize these contacts?

LP: Moore has described his encounters in some detail – look for Unearthing and the first Moon and Serpent CD, and the series Promethea for what looks a lot like a thinly-disguised narrative account of his experiences. Ideaspace is inhabited, it’s alive. Gods, as he says, inarguably exist in the imagination, if nowhere else. If the streets of Northampton map into Ideaspace, so do its inhabitants, so do all sorts of things. Metropolis and Superman are as real in Ideaspace as Birmingham. Moore’s encounters, and comparing notes with other practitioners, have led him to conclude that these entities have some form of independent existence, as different people have met them.

My own view … there is clearly a specific type of common experience that a fair number of people have had. A moment of encounter with something huge and strange, and difficult to process. Moore’s experiences, as he’s noted, are very similar in places to Philip K Dick’s Valis experience, to things William Blake talked about, and to things that shaman in many cultures have talked about since the dawn of history. What that is … I don’t know. I think, inarguably, there’s a ‘UFO phenomenon’. Thousands of people recall very similar experiences of awe, abduction, violation, epiphany when encountering an ‘alien’. At the absolute most skeptical, all-of-them-are-delusional, level of explanation, there is something that needs explaining. And there might be a perfectly rational reason to do with cultural conditioning and everyone seeing Close Encounters and at least one episode of the X-Files. But it’s still a thing. I think that Moore’s experience is probably the same sort of thing the Christian mystics had – the brain suddenly doing something that seems to put it in contact with vastness, something too big to take in, something that takes decades to process. Cultural conditioning, or actual contact … I’m inclined to think the former, but I’m not so arrogant that I know that.

Moore’s keen to talk about his magic helping him creatively, he uses it to talk about big issues like consciousness, death and the limits of knowledge. What he’s far more evasive on is how it feels to him. And I’m not a mind-reader and I’m always really suspicious of people who assert what another person thinks or feels. That said, I think in an odd way it’s kept him sane. It’s allowed him to reconcile different aspects of his life. I think it was suddenly earning a lot of money and being on the telly for writing Batman stories that was the thing that messed up his brain and his relationships. The question becomes one of whether he’s using these great powers for good, or in the best way he might. It seems to make him content, it has inspired some great art, it’s dramatically expanded the number of subjects he’s interested in and knowledgeable about. I mean, that sounds like it ‘works’, doesn’t it?

Lance Parkin is a British author, best known for writing fiction and reference books for television series, most notably Doctor Who. He is an Alan Moore completist, having followed the comics maetro’s career since the 1970s, and in 2001 he wrote an acclaimed guide to Moore’s work, which has since been updated and reissued. In addition to contributing pieces to magazines such as TV Zone, SFX and Doctor Who Magazine, he is also the co-author of Dark Matters, a guide to Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy.

That’s a great interview. Thank you. Alan Moore is a fascinating guy…brilliant.

You’re most welcome. I agree – Moore and his work are larger than life. When combined with the wonderful and unique biography that Parkin wrote, an interview was in order.

You must log in to post a comment. Log in now.